elcome to the digital dark ages.

elcome to the digital dark ages.

To load this webpage on your browser, thousands of bytes are transmitted to your device—whether on your desktop computer, laptop, or smartphone. But centuries from now, it may look very different. Your future Wi-Fi honing gizmo may display the GIFs and images in a garbled mess, riddled with broken links and unsupported animations. The site might not even exist at all.

This dark age—where obsolete technology renders 21st-century history an incomprehensible digital soup—spawns from a myriad of digital dilemmas. The disappearance is partly a problem of having too much of it. With more people on planet Earth creating an increasing amount of digital content—text messages, emails, videos, photos, tweets—we’re submerged in what Annalee Newitz, editor at large at Ars Technica, calls a “data glut.” There is simply too much information to manage. And the digital mountain of information will just keep growing. By 2025, some analysts expect us to create 10 times the data we produced in 2016.

But under the weight of the information overload there lies a more imminent issue: long-term storage and preservation. Researchers are finding ways to pack more data onto digital storage, but new techniques may not keep pace with the tidal wave of new information we generate.

“We are in the information glut now and freaking out and we have no idea what to do with it,” Newitz says.

With every new and more-efficient storage solution, there’s a risk that previous technologies become obsolete. To alleviate these pressures, researchers are trying to build better storage containers—time capsules that could help data live forever.

n 2005, historian Doris Kearns Goodwin released her Pulitzer Prize–winning book, Team of Rivals, a biographical portrait of President Abraham Lincoln and his cabinet. She assembled a dialogue, giving voice to the long-gone historical figures. To create an accurate representation of the debates and issues of the time, she transported herself to the mid-1800s by poring over primary sources preserved in libraries all around the United States.

n 2005, historian Doris Kearns Goodwin released her Pulitzer Prize–winning book, Team of Rivals, a biographical portrait of President Abraham Lincoln and his cabinet. She assembled a dialogue, giving voice to the long-gone historical figures. To create an accurate representation of the debates and issues of the time, she transported herself to the mid-1800s by poring over primary sources preserved in libraries all around the United States.

“Imagine a 22nd-century Doris Kearns Goodwin going back to look at the beginnings of the 21st century,” says Vinton G. Cerf, vice president and chief internet evangelist at Google.

Decades from now, a historian (or digital archaeologist) who may want to reassess the political climate of 2017 must rely on a different suite of more incomplete sources. Deleted tweets, forgotten email chains, web pages with broken URLs, electronic files that can no longer be read on the programs of the day. These digital artifacts all stand in the way of piecing together any kind of narrative. Pieces of data vanish and become sucked into what Cerf describes as an informational black hole.

“All the digital artifacts that we have created today in the beginnings of the 21st century will no longer be accessible in the 22nd century,” Cerf says. The Doris Kearns Goodwins of the future “will all look at us as a black hole.”

In a future world of obsolescence, digital objects of the past could be lost due to the disappearance of the original programs and machines that read them—the data gobbled up by the informational black hole. For example, files once readable on floppy disks become increasingly harder to retrieve as readers become more of a vintage item.

“We’re like nautiluses,” says Cory Doctorow, science fiction writer and author of books like Walkaway and Little Brother. “We go from one device to the next and the next one because storage keeps getting so cheap, [and] has twice as much storage [as] the last ones we had.”

The result: a trail of vulnerable data, which can become unsalvageable if not maintained properly. Not all data may need to be preserved, but the potential loss and disappearance of certain information could pose a risk to maintaining a coherent picture of the digital age. And with our current fixation on upgrading hardware every few years, the problem is getting worse.

In order to prevent us from spiraling further into the informational black hole, researchers are on the hunt for ways to immortalize history—a system to eternalize data forever.

“All the digital artifacts that we have created today in the beginnings of the 21st century will no longer be accessible in the 22nd century.”

mmortal data is a germ of an idea. Some see it as one component to fixing the issues with data preservation, like Richard Whitt, corporate director for strategic initiatives at Google and manager of Google’s Digital Vellum, a team that investigates preservation issues.

mmortal data is a germ of an idea. Some see it as one component to fixing the issues with data preservation, like Richard Whitt, corporate director for strategic initiatives at Google and manager of Google’s Digital Vellum, a team that investigates preservation issues.

With any complex issue, there is no “single silver-bullet solution,” says Whitt, who wrote a January 2017 report that explores the challenges of storing and preserving data for hundreds of years. The sole responsibility should not fall upon one organization or company. Preservation strategies and technologies should complement each other to build an evolving, more everlasting storage system, he writes.

For instance, “there are business models that Google could actually employ to preserve content for the long term, essentially preserving what you have with Google forever,” Whitt says by phone. “But it can’t just be Google alone, and not just even the United States. It really has to be a global concern.”

A small but growing renaissance within the data storage field has emerged. Researchers around the world specializing in everything from computer system architecture, biology and molecular sciences to experimental physics have found themselves working on technologies to address the digital dilemma.

Currently, data that needs to be preserved for the long term is stored on dense mediums such as magnetic tape. However, there’s a physical limit to how much data can be packed on to today’s storage technologies. “We are reaching the point where the individual grains on our hard disks or the individual components in the flash memory are getting so small that it will have to fail very soon,” says Sander Otte, a fundamental physicist.

Researchers are in the early stages of developing an array of new, denser storage materials. Engineers, chemists, and physicists have created a nanoparticle liquid suspension to store a large volume of data in a tiny space, and began experimenting with defects in diamonds that can do the same. A group at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom developed a durable, coin-sized quartz disc that could store up to 360 terabytes, and has the potential to keep the data for billions of years, according to the researchers.

Others have even begun mastering data storage at the atomic level.

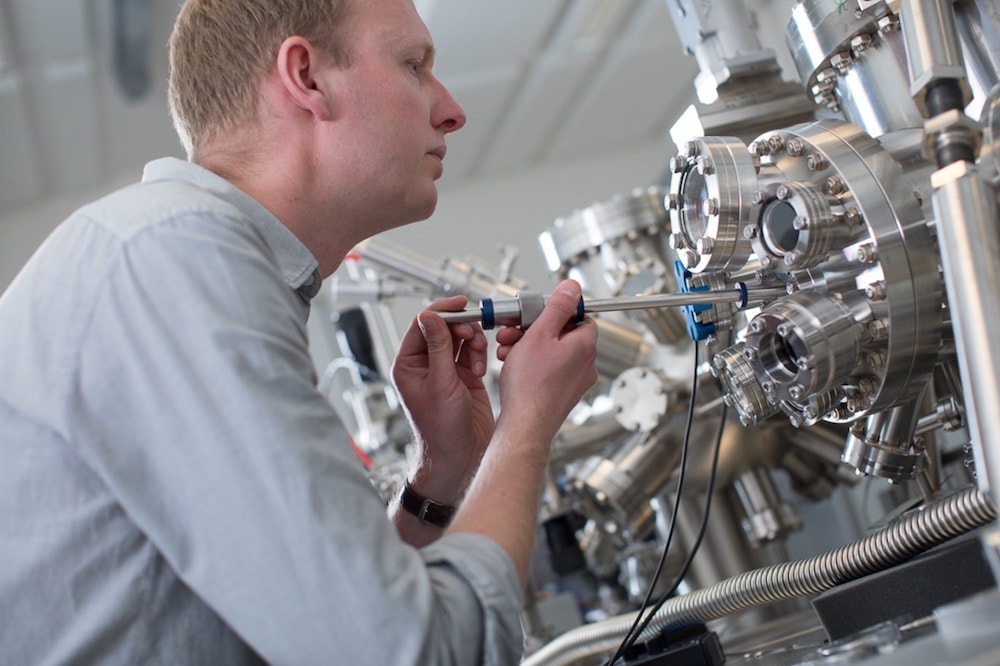

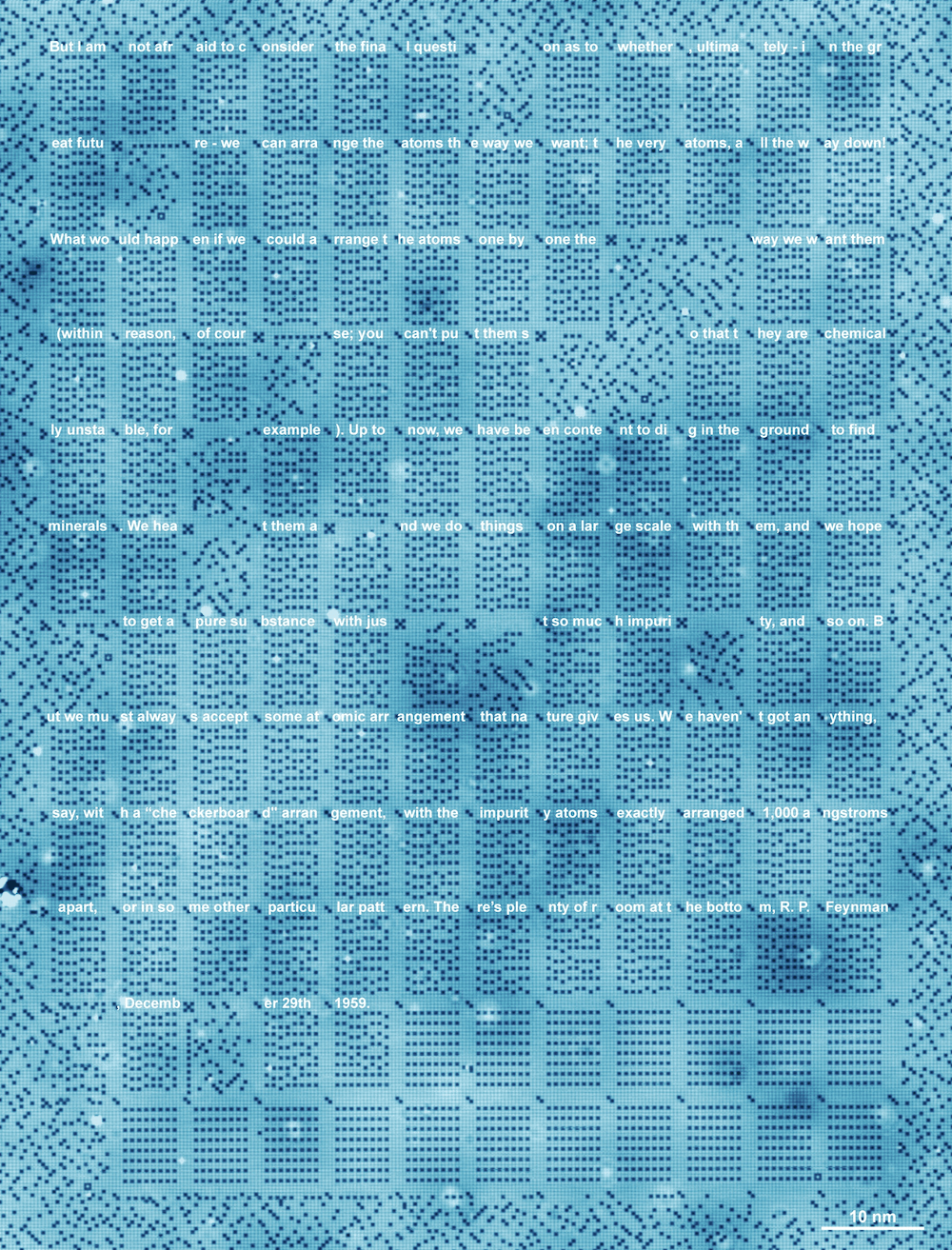

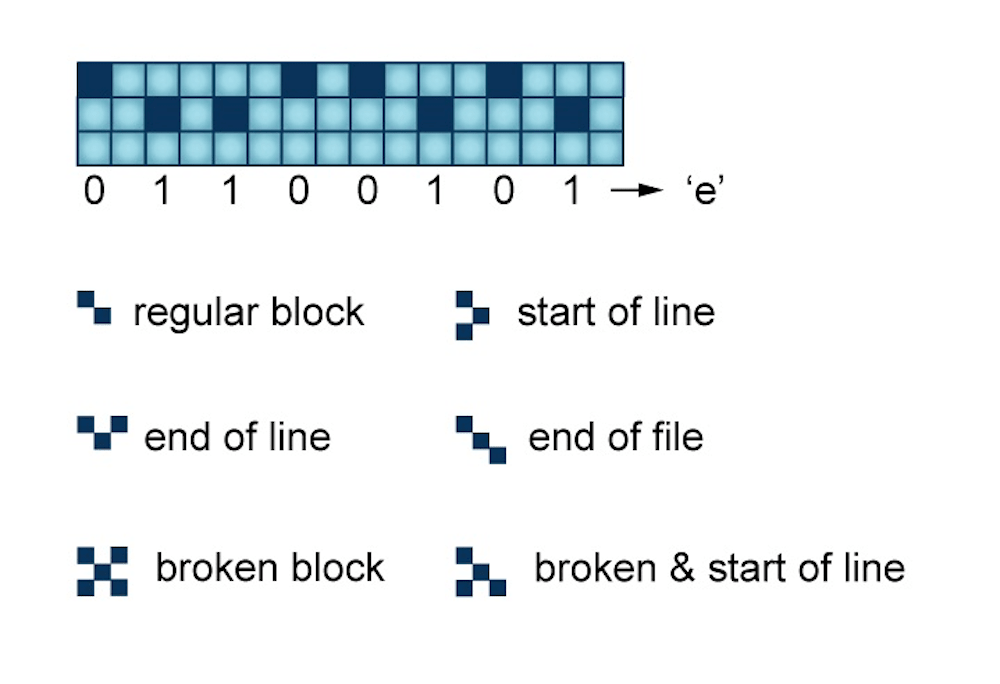

Otte and his colleagues at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands were using different combinations of metallic surfaces and atoms to conduct quantum experiments when they realized their atomic apparatus could also store bits of information. The atomic “puzzle-box slider,” as Otte describes, is made of copper crystal and covered with a layer of chlorine atoms. Like a grid, the chlorine atoms spread out and fill in plots on the copper substrate. However, some holes were left between atoms because there wasn’t enough chlorine added to form a complete layer. With what was essentially a very sharp needle, the team was able to probe the atom and slide it over the surface.

Scientists learned how to move atoms around 1989. IBM scientists spelled out the company name by moving Xenon atoms, and later in 2013 even created a short film out of atoms called A Boy and His Atom: The World’s Smallest Movie. But Otte and his team found that they could store information on the apparatus, sliding and moving the chlorine atoms up and down into the empty plots of the grid, creating the zeros and ones that make up bits of data.

Otte estimates that they could theoretically scale up atomic storage to keep all the books ever written on a medium the size of postage stamp. The density of data that can be contained with atoms could be the highest one we may ever physically be able to achieve, Otte says.

However, there are major disadvantages of atomic data storage at this stage in the research, he adds. The entire experiment must be done in a vacuumed space because the metal surface could oxidize if exposed to oxygen; the slightest vibration could disrupt the needle and destroy everything on the surface; and it needs to be done at low temperatures or the atoms would move on their own.

Another potential tool at the microscopic level has caught Otte’s interest: DNA.

“What I love about DNA is that all the tools are already there,” he says.

NA, the fundamental molecule key to the basis of life, has had billions of years to perfect itself.

NA, the fundamental molecule key to the basis of life, has had billions of years to perfect itself.

“It’s amazing that nature has actually evolved a bunch of basic molecular mechanisms that can be used to build synthetic information systems,” says Luis Ceze, a computer scientist and computer architect at the University of Washington.

The idea that DNA could become a kind of “living library” that can hold the world’s data has been floating around since the 1960s after the structure was finally understood by James Watson and Francis Crick in 1953. Its super-rich density, stability, and efficiency has made DNA an appealing candidate for future data storage.

However, until recently, the technology was too slow, imprecise, and impractical to store data onto the sequence of nucleotide bases.

Separate groups at Harvard University in 2012 and the European Bioinformatics Institute near Cambridge, U.K., in 2013 both successfully demonstrated storing data onto synthetic DNA. While the bit amount that fit on the DNA during these first studies was on the magnitude of hundreds of kilobytes, the potential density is almost unfathomable.

“Everything that somebody with a computer would be able to access on the internet [without a password], that whole thing can be archived in something that’s a little bigger than a shoebox,” says Karin Strauss, a computer architecture researcher at Microsoft and affiliate professor at the University of Washington. “If you were to do it with any other technology, it would be at least 1,000, if not 10,000, times bigger.”

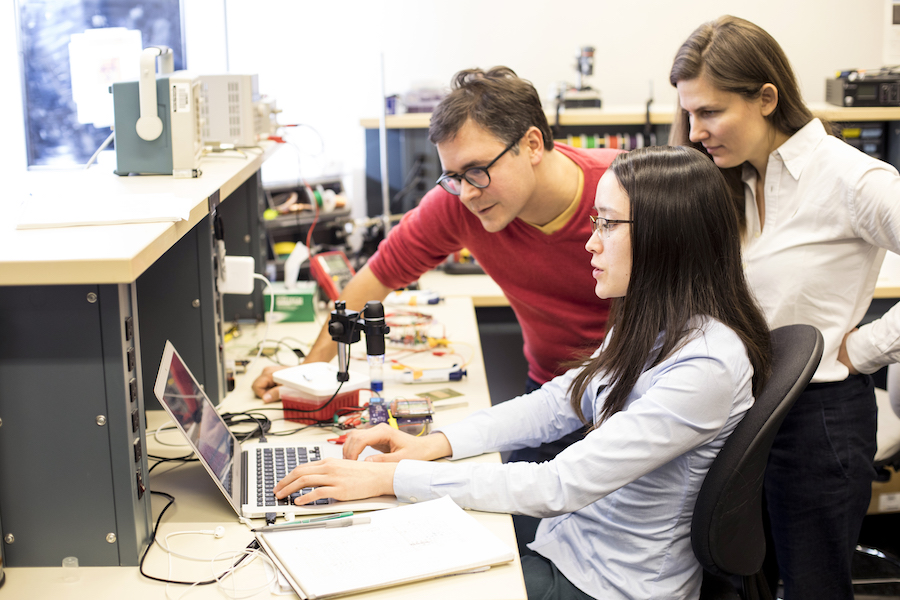

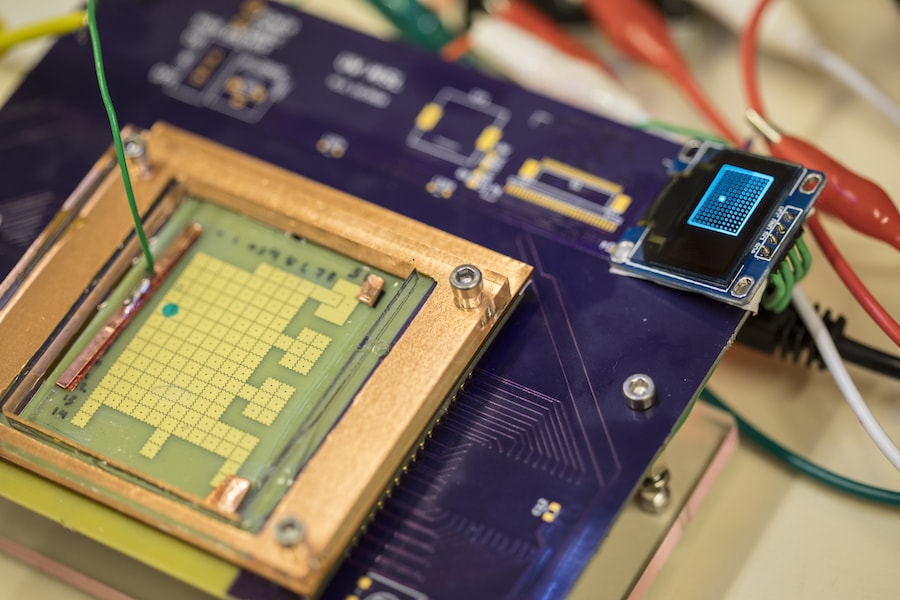

In 2014, Ceze and Strauss teamed up in a joint collaboration between the University of Washington and Microsoft to investigate what an entire DNA storage system might look like in the near future.

DNA can be one possibility for the last level in the hierarchy of a storage system, says Ceze. “Your data goes from flash to disk to tape, and then you go to DNA as the last layer.”

For this to work, DNA will reside in a system composed of electronic and molecular components. The molecules will need fluidic systems for these to connect with each other, Ceze describes.

To encode the data and manipulate the DNA, the molecule must be in solution, Strauss explains. The team of computer scientists and molecular biologists “translate” the sequence of zeros and ones of the data file into the four nucleotide bases, adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine, Strauss says. Each base corresponds to a pair of digits. For example, adenine could code for 00 and cytosine for 01. Once the researchers come up with the sequences to describe the original bits, they then fabricate the synthetic DNA.

The synthetic DNA allows for more control and customization, and is much safer to use than genomic DNA extracted from living organisms, Ceze explains. For example, the researchers can avoid too many repeated bases or patterns in the DNA sequence. The molecule—while it has existed for billions of years—can also be fragile. Even at rest, it can be prone to denature or unwind under high temperatures, light, and humidity. The researchers stabilize the DNA through dehydration and treating it with synthetic chemistry processes. The packaging rests within the larger storage bank, protected from the surrounding fluidic structure of the system.

Already, billions of copies of books, all 154 of Shakespeare’s sonnets, image files of various sizes, and most recently a clip of a galloping horse from an 1878 film have been stored on DNA successfully. To Strauss and Ceze’s knowledge, the team currently holds the record for storing and fully recovering the most amount of data on DNA at 400 megabytes—not an easy feat given the errors that can come up in DNA sequencing, Ceze explains.

“Now that we know how to read DNA, it’ll be eternally relevant because we will always have readers to read it.”

Data recovery from the molecule has been one computational problem research groups have encountered, and they continue to look for ways to streamline the process. In the 2013 European Bioinformatics Institute study, two sequences containing 25 nucleotides were lost, while the Harvard group in 2012 had to go back and manually correct ten bits of error. To reduce errors, the researchers add in some redundancies to the sequence to help with recovering the information as it was originally, Strauss explains.

DNA might just be the key to preserving human history—a tiny molecule that will withstand time as long as there is life on the planet, Strauss says. Technology obsolescence is no longer a threat to data when the information lives on a medium that will always be read.

“Now that we know how to read DNA, it’ll be eternally relevant because we will always have readers to read it,” she says.

The molecule itself does have a shelf life of 6.8 million years if kept at ideal preservation conditions, and ceases to be readable at roughly 1.5 million years due to the decay of the strands. While it lasts much longer than any medium currently used on the market, DNA storage remains a costly option in comparison to other long-term storage, such as magnetic tape, which has a lifespan of 30 to 50 years.

While many researchers are optimistic about the possibility of using DNA to store nearly unlimited amounts of information seemingly forever, Annalee Newitz isn’t so sure. “I love the idea that our bodies could become libraries,” she says. “But then of course they are even more vulnerable to data loss and the ravages of time.”

And perhaps, she suggests, we’re deluding ourselves by even trying to find a way to create ‘immortal data.’

“This idea of ‘digital storage is forever,’ or ‘digital storage means we can take every piece of human knowledge and put it in a tiny box, and everyone will have access to it,’ those are lies,” she says. “They are very hopeful, wonderful lies. I wish they were true, but as we’ve seen throughout history, libraries burn, film decays, data decays.”

But if history is any guide, we’ll keep looking for more and better ways to keep our stories. We’ve spent centuries trying to find the best, most reliable way to save information—from Babylonians scratching out beer rations on clay tablets, to magnetic tapes containing petabytes of particle physics data, to the internet, which holds and has been the breeding ground for entire digital cultures. For most people, part of our lives exists only in the digital world, whether you like it or not. Nestled in the arbitrary sequences of ones and zeros are moments of modern daily life. And each piece of data makes up our digital history.

The quest for immortal data manifests from the same reason we save old artifacts, personal keepsakes, and family heirlooms. It comes from our desire to transcend time, to live on in some shape or form through the objects we leave behind. Despite the challenges looming in the digital dark age, people will continue searching for that sip of digital ambrosia, whether that’s DNA or another medium yet to be discovered.

Written by Lauren J. Young

Design by Daniel Peterschmidt

Edited by Brandon Echter

Fact checking and copy editing by Michele Berger

Animated titles by Cat Frazier

Sidebar GIFs and in-text letters courtesy of The GifCities Project from The Internet Archive

Cover video via Shutterstock

Special thanks to Christian Skotte, Rachel Bouton, Danielle Dana, Johanna Mayer and the rest of the Science Friday staff, Alex Newman, and Terence Collins.

Published: December 15, 2017

The text was updated on January 2, 2018 to reflect the following change: Defined the role of Sharon Newman, a research scientist and former project member at the University of Washington.