n December 1, 2016, Debbie Rabina clicked through a long list of URLs on her laptop. She hunkered down in the Hartwell Room on the third floor of the New York Academy of Medicine in Manhattan, a home safeguarding over 550,000 volumes of anatomical atlases, early scientific texts, and other medical books and artifacts. She combed through hundreds of U.S. federal government websites and carefully evaluated each to determine whether or not to flag it for preservation. Similar to the librarians who preserve medical history at the New York Academy of Medicine, Rabina was helping to create a snapshot of our digital history during the contentious 2016 U.S. presidential election.

n December 1, 2016, Debbie Rabina clicked through a long list of URLs on her laptop. She hunkered down in the Hartwell Room on the third floor of the New York Academy of Medicine in Manhattan, a home safeguarding over 550,000 volumes of anatomical atlases, early scientific texts, and other medical books and artifacts. She combed through hundreds of U.S. federal government websites and carefully evaluated each to determine whether or not to flag it for preservation. Similar to the librarians who preserve medical history at the New York Academy of Medicine, Rabina was helping to create a snapshot of our digital history during the contentious 2016 U.S. presidential election.

She ticked off the criteria on her checklist:

Does this website have important scientific data or information?

Has it already been added to the nomination list and backed up?

How much is it in danger of disappearing during the new administration?

“There’s a lot of information that the administration can take down from different executive websites and still be within the bounds of the law,” Rabina says, who teaches and researches public access to government information at Pratt Institute’s School of Information at the university’s Manhattan campus.

As the 2016 presidential campaign heated up, digital preservationists as well as scientists and researchers, like Rabina, began to wonder what might happen to the thousands of datasets and articles published on government domains, particularly the information that did not align with the agenda of President Donald Trump’s administration.

“This administration made it very clear what their priorities are during the election, and they also made it very clear that they are going to proactively withdraw things out of the public domain and disengage from the public when it comes to information,” Rabina says.

Rabina, a former librarian, was compelled to act. After a conference at the New York Academy of Medicine, she and a few colleagues hosted one of the very first pop-up URL harvesting events for the End Of Term Web Archive, a project run by a consortium of universities and institutions that archives all kinds of government information at the end of every four-year presidential term.

As one administration goes out, a new wave of online domains comes in. But the vulnerability of online data is not limited to government websites. It’s a common thread that weaves throughout the entirety of the web.

n a grandiose, white brick-and-mortar, former Christian science church in San Francisco, librarians are building what founder Brewster Kahle calls “the Library of Alexandria, version two,”a virtual, utopian archive for the digital age that holds over 20 petabytes of data.

n a grandiose, white brick-and-mortar, former Christian science church in San Francisco, librarians are building what founder Brewster Kahle calls “the Library of Alexandria, version two,”a virtual, utopian archive for the digital age that holds over 20 petabytes of data.

“The Greeks had a broad vision—encyclopedia, all knowledge,” says Brewster Kahle, a digital librarian and the founder of the Internet Archive. “But the Library of Alexandria was only available to those who could get there. Could we do that, but make it that anybody, anywhere can get access to it?”

Providing continued public access to information comes with an array of challenges, especially with the fluctuating landscape of the internet.

Everything born in the digital world is at risk of disappearing. You may think or feel that your embarrassing pictures or song lyrics posted in middle school or tweets riddled with typos and misspellings will live forever (and maybe come back to haunt you). But the things you’ve uploaded and said on the internet are a lot less permanent than you think.

“The average life of a web page is 100 days before it’s either cleaned or deleted,” Kahle says.

The internet’s dynamic, ever-growing structure was never built to store information for too long. Links break. Domains become defunct. Content is prone to drift. Pages become vulnerable to vanishing from web.

“People have the expectation that something online will always be online, or that if they took a digital photograph, they’ll always be able to get it, even 20 years later,” says Jefferson Bailey, the director of web archiving programs at the Internet Archive who spearheaded the organization’s participation in the recent End Of Term Web Archive harvest. But online, “that’s not the case.”

Traditionally in physical collections, librarians gather and provide access to manuscripts, photos, and journals—items that surprisingly have a much longer shelf life than many digital files. On the internet, digital librarians continue to preserve our history, but must first navigate through a labyrinth of dispersed personal accounts on the web that have come and gone through time.

“People have the expectation that something online will always be online,” says Jefferson Bailey. But, “that’s not the case.”

Increasingly in our digital-first world, the pieces of information born digital are without an original physical container, leaving them to die in the virtual realm.

“The vision of the internet as a library right now, it's not that,” Kahle says. “Right now, it is a really convenient communication tool. It’s got something on everything. It’s got a Wikipedia page on lots and lots of stuff, but the depth is not there.”

Already, important keystones of the internet’s history have seemingly evaporated from existence. There are innumerable accounts of disappearing data (big and small), from award-winning web features to online forums to significant digital artifacts that tell the origins of the World Wide Web.

CERN, the European research and particle physics laboratory, created the very first website in 1990. For decades it was lost, and was only resurrected back to its original URL in 2013. However, the site is a reconstructed shell of its original form—rebuilt from the oldest copy that could be found.

“History doesn’t always bequeath things to us intact,” says Kari Kraus, an associate professor in the College of Information Studies at the University of Maryland. “We might not have an entire medieval church to save, but we have a steeple or the entire base, we’ve got fragments or shards. Likewise in the digital realm, we often end up preserving components or pieces of a larger whole.”

Similar to scribes duplicating text in a codex over time, every backup or copy of a file may not always be the same, Kraus explains. There is a mantra in digital preservation that a lot of copies keeps information safe, she says. Still, errors can be introduced or alterations can be made in copies. This causes some to question the genuineness, trustworthiness, and authenticity of digital information.

But that doesn’t stop some digital archivists from trying to preserve the web.

The Internet Archive receives about 20 website nominations per second, and saves 4 to 5 billion pages a week. Its Wayback Machine curates snapshots of a site’s life throughout time. In addition to the more than 380 billion saved websites, the Internet Archive has also made available millions of books, movies, music, and old software and programs, such as WordPerfect, The Oregon Trail, and a virtual arcade of video games. Last year, the Archive brought back some 90s nostalgia by extracting every gif from the forgotten and lost GeoCities—a once popular web hosting service which sunk into obscurity when Yahoo closed it in 2009.

“If you’re collecting on the web, you can basically get stuff from anyone who’s publishing on the web—and that can be marginalized communities or teenage poetry blogs,” Bailey says. “So you can get a much more pluralistic, diverse archival record than you used to be able to when you had to go and take it out of an office or take it out of somebody’s garage.”

And anyone can nominate a page to be archived on the Wayback Machine.

“We’re trying to fix the web,” Kahle says simply. “We all know something that should be preserved and I think we’re now alerted that things go away just for technology, but also for political reasons.”

istorically, every change in power places libraries in a position of danger. The Library of Congress was reportedly burned in the early 1800s by the British; the Grand Library of Baghdad was destroyed during the invasion of the Mongols; most famously the Library of Alexandria was accidentally torched when Caesar took over.

istorically, every change in power places libraries in a position of danger. The Library of Congress was reportedly burned in the early 1800s by the British; the Grand Library of Baghdad was destroyed during the invasion of the Mongols; most famously the Library of Alexandria was accidentally torched when Caesar took over.

“Sometimes it’s accidental, but it’s rarely that,” Kahle says. “It’s usually the new guys don’t want the old stuff around.”

The same vulnerabilities apply in the United States.

“Things disappear with every presidential election,” Rabina says. “As someone who has been teaching this for many, many years, I could tell you that it’s a nightmare to update my slides every time there’s an election change because none of the links work. They just all go away.”

But 2017 was different. Not only was there more government information online than ever in history, the priorities had never been so completely opposite of the previous administration.

“These two pieces make the information that exists through the government more vulnerable than it has been in the past,” says Margaret Janz, a data curation librarian at Penn Libraries and one of the co-organizers of the data rescuing project, Data Refuge.

“Sometimes it’s accidental, but it’s rarely that,” Brewster Kahle says. “It’s usually the new guys don’t want the old stuff around.”

People were concerned about access to all kinds of data—climate change, census, food and safety, reproductive health, LGBT rights and civil rights. And within weeks after President Trump took office in January 2017, there were several reports that government-provided information and web pages had been altered, shifted or buried in other sections of the site, and temporarily or permanently removed.

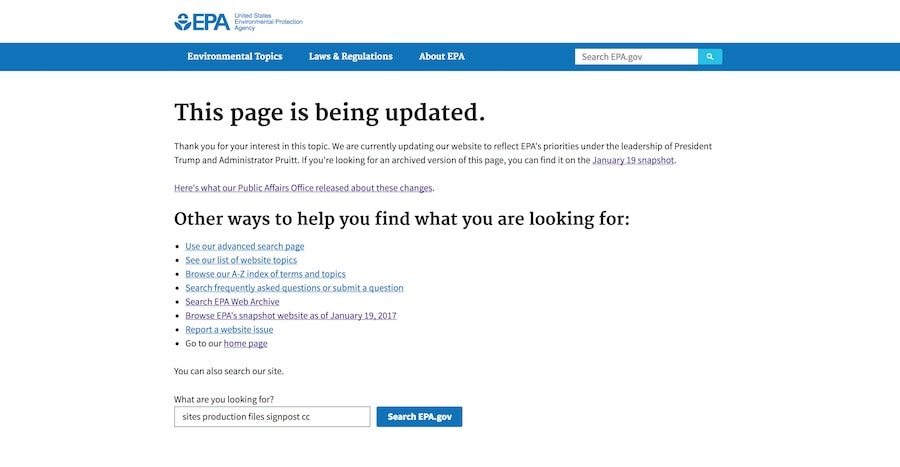

On April 28, 2017, for instance, the Environmental Protection Agency took down its site “Climate and Energy Resources for State, Local and Tribal Governments”—a site that provided information for local governments on how to take action on climate change, among other resources. The page, and similar ones, was taken offline and replaced with a temporary message that read: “We are currently updating our website to reflect EPA’s priorities under the leadership of President Trump and Administrator Pruitt.”

When the site was republished a few months later, it had changes that raised red flags among environmental organizations and researchers.

According to an October 2017 study by the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI), the newly launched domain omitted “climate” from its title, and approximately 15 mentions of “climate change” from the main page. There were less resources and links related to climate and climate change, and the 380 page site was cut to 175 pages.

This is one of many notable changes that the EPA website has undergone since January 2017, which has also included the removal of other web pages, PDFs, and phrases such as “climate change” and “clean energy.” Some climate change information still exists, if you know where to look: Content has drifted to other areas of the site or has become lost with pages that were deleted. These alterations have caused “significantly reduced” public access to resources, says Toly Rinberg, who helps lead website monitoring at EDGI—an organization that continues to track changes to over 25,000 pages hosted by environmental agencies, including the Department of Energy, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and EPA.

It's been more than six months since the April 28, 2017 revision of the “Climate and Energy Resources for State, Local and Tribal Governments” website, and there are still several other EPA domains that are still “updating,” Rinberg says. It could be possible that we may see similar cases.

Currently, the EPA is redirecting users that cannot find formerly available information to a snapshot of the site when the agency was still under former EPA administrator Gina McCarthy. However, the two versions may confuse the public, says Rinberg.

“It’s important to remember that for the average visitor of sites, they’re not going to spend time thinking about what did this website look like six months ago, a year ago,” he says. “The public doesn’t even know what used to be here and what they may have had access to but no longer do.”

In another instance, during the wake of Hurricane Maria in September 2017, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s website published statistics that half of Puerto Ricans had access to drinking water and 5 percent of the island had electricity, the Washington Post reported. Those were the numbers on Wednesday, October 4. But the next morning, those metrics could not be found anywhere on the page. The information has since been put back on FEMA’s site, and can also be found on the website of the office of Puerto Rican Governor Ricardo Rosselló.

However, the temporary removal of the statistics is “a very upsetting example” of why it’s important to ensure continued access to government data, Janz says. Blocking public access could stall things like disaster relief efforts, scientific research, and even city planning projects.

“Community planners are using this data to make decisions about where to put certain amenities, where to put certain buildings,” Janz says. “If this administration doesn’t want people to have [certain] data because it contradicts their agenda, how can we make sure it’s still available? Because we really do need this data to not just continue the science, but to help our communities.”

The End of Term Web Archiving drew in more attention from the media than any previous U.S. administration turnover since the project began in 2008 during the change from the Bush administration to the Obama administration. The potential loss of public access to billions of bytes of government data made people realize just how fragile the current structure of the internet is.

It also put the librarians and digital preservation under the spotlight. Some made comments that the intensive archiving was unnecessary, and that those involved were “all hysterical” and “being overly political,” Janz says, while others saw these stereotypical “old, frumpy” librarians as vigilantes, activists, hackers, and superheroes, Rabina says.

Suddenly, as more people became excited about the archiving, the work librarians had been doing forever “became sort of sexy and trendy, and you could call it different things like ‘rescue’ and ‘capture’ and ‘save’ and ‘Wonder Woman to the rescue,’” says Rabina. “I’m very tickled that all these hipsters now think that this is sexy work, but you know this is all a little mundane work sometimes. It’s like writing a lot of citations and footnotes.”

A quiet book-lined room full of librarians performing the task of archiving websites—URL by URL—may not have been the most riveting scene to onlookers, as Rabina describes. However, the duty of ensuring the longevity of digital information places a heavy burden on a small community.

At various data rescuing events across the U.S., volunteer librarians nominated and identified URLs they thought were at risk or were worth saving, including agency sites and social media posts. Then, the websites would be backed up in digital repositories hosted by various partner institutions such as the Internet Archive, the University of North Texas Libraries, and even the Library of Congress.

“We try not to feel too guilty of missing something,” says Abigail Grotke, a web archivist at the Library of Congress who also collaborated on the 2016 End Of Term Harvest. “We do the best we can with the resources we have.”

At the Library of Congress, archivists often revisit all kinds of websites on the internet over time using crawlers, or “spider” bots that move through the web and copy or scrape pages. The bots systematically visit sites and download content like a search engine, explains Grotke.

Crawling the web can sometimes be slow and tedious work. However, archiving some types of digital content brings about an air of urgency. Particular time sensitive events require web archiving, like the Olympics, government campaigns (sites that are notorious for being quickly removed or changed shortly after the election), and the end of term, Grotke explains.

“We know there's this sort of deadline over the inauguration when things are going to change,” Grotke says. “So there is a frenzy of activity to preserve in that time period.”

In the previous 2012 cycle, the End of Term Web Archive captured 3,247 websites and 21 terabytes of data. By the end of the 2016 harvest, 11,382 websites were nominated to be saved. The official numbers of what has been collected has yet to be released, but within just the Library of Congress, volunteers, librarians, and partners collected about 155 terabytes of government web content and data, Grotke estimates, while the Internet Archive worked on a related project storing 100 terabytes.

t’s still virtually impossible to get every bit of data, Grotke says. For instance, government websites alone host a lot of data (Janz estimates on the petabyte level at the very least), which puts the archivists at technical odds.

t’s still virtually impossible to get every bit of data, Grotke says. For instance, government websites alone host a lot of data (Janz estimates on the petabyte level at the very least), which puts the archivists at technical odds.

The web crawlers can’t collect certain kinds of data. Since the bots are programmed to crawl the web like a search engine, they encounter issues with forms that must be filled out, interactive pages, or streaming media, for instance.

Independent data rescuing projects like Data Refuge, by Penn Libraries and the Penn Program in the Environmental Humanities, assisted the End of Term Web Archive’s efforts. During Data Refuge’s events, “data rescuers” were able to nominate pieces that the End of Term Web Archive wouldn’t be able to get to or its crawler couldn’t pick up, Janz says.

Skilled data rescuers would download or “scrape” the data, where “they have to pull some kind of script to pull the data out of the site,” she explains.

“Nothing is very static on the web. So in order to capture changes in websites, we have to constantly try to archive it.”

Digital librarians also encounter challenges with privatized or closed content. Some social media and services like Facebook can’t be crawled easily, says Bailey. The Internet Archive does collect social media, but Facebook, in particular, “seemingly intentionally makes it challenging,” he says. Similarly, apps create highly blocked-off environments.

Bailey calls these kinds of sanctioned communities and content “walled gardens.” From a business standpoint, the walls are there for your personal protection and privacy, but it makes it difficult for archival practices. Our digital history may end up being a disjointed record of our culture as a result.

“We’re going to have a very strange view of the early 21st century, and in some sense all sorts of details will be recorded, but some of the very important things will not be recorded,” says Kahle, who supports a more open access outlook on the web.

More and more data is born natively in a digital environment. If it isn’t saved by archivists, the data dies on the internet—seemingly difficult to near impossible to recover.

“It’s the wild, wild west in terms of what’s out there,” says Grotke. “Nothing is very static on the web. So in order to capture changes in websites, we have to constantly try to archive it.”

It’s been a little over a year since the data harvesting began. As of now and according to Toly Rinberg of EDGI, pages have been cut and altered, but no data sets have been removed from environmental government agency sites. Only a few reports on animal welfare that were scheduled to be taken down before President Trump’s inauguration have been deleted (and are slowly making their way back online after public outcry), as well as the Department of Energy staff directory and a climate modeling tool from the Department of Transportation (which luckily the Internet Archive saved), Janz says.

So far to Janz’s knowledge, there have been very few to no requests for the government data archived during Data Refuge’s rescuing events. She sees it as a good thing that nobody has needed the data that was saved. But the efforts weren’t fruitless.

“We’ve learned a lot about how government agencies are creating this data, how they back things up, how vulnerable they view it,” she says.

he upending of government data and websites is part of a larger systemic problem, one that librarians have been struggling with for decades.

he upending of government data and websites is part of a larger systemic problem, one that librarians have been struggling with for decades.

On a daily basis, digital and web librarians sift through the deluge of data. When the web archiving program first started at the Library of Congress, the amount of data managed was small, Grotke says. Now, the archivists have over a petabyte (a million gigabytes)—bringing in about 20 to 25 terabytes (a thousand gigabytes) a month.

And as the amount of online content and the size of websites continue to grow exponentially, they must make executive decisions on what to save and what to sacrifice.

Still, not every bit of data can be salvaged, and not every bit of data necessarily needs to be saved, Grotke explains. What’s kept are the most significant snapshots of what’s happening on the internet right now. And, hopefully, those snapshots will help people in the future: “Our collections will probably be really valuable in about 50 years when some of these websites are really long gone,” says Grotke.

While the internet is a much more unpredictable environment to build an archive out of, the principles of librarianship remain the same. Humans stockpile and organize information to conquer time, says Kari Kraus of the University of Maryland. And librarians will continuously work to come up with new ways to preserve our digital history.

“I like to think of collection as a service,” Rabina says. Just because information may be free now, it doesn’t mean it’ll be free forever, she says. “If you don't collect, it's going to disappear.”

Written by Lauren J. Young

Design by Daniel Peterschmidt

Edited by Brandon Echter

Fact checking and copy editing by Caitlin Cruz

Animated titles by Cat Frazier

Sidebar GIFs and in-text letters courtesy of The GifCities Project from The Internet Archive

Cover video via Shutterstock

Special thanks to Christian Skotte, Rachel Bouton, Danielle Dana, Johanna Mayer and the rest of the Science Friday staff, Alex Newman, and Terence Collins.

Published: December 15, 2017

The text was updated on December 16, 2017 to reflect the following changes: The University of North Texas Libraries, not the University of Northern Texas Libraries, was a partner institution with various data rescue events.